(For previous episodes scroll down)

Dateline: Mid-November 1917, Estrée Blanche, north-eastern France.

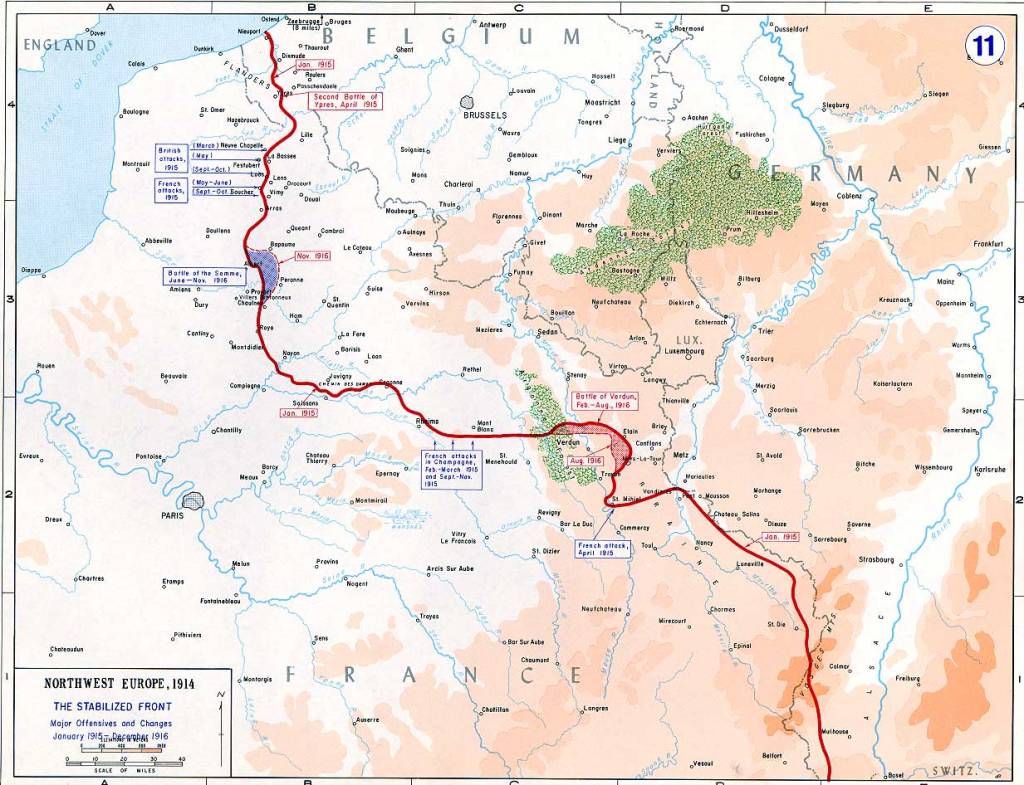

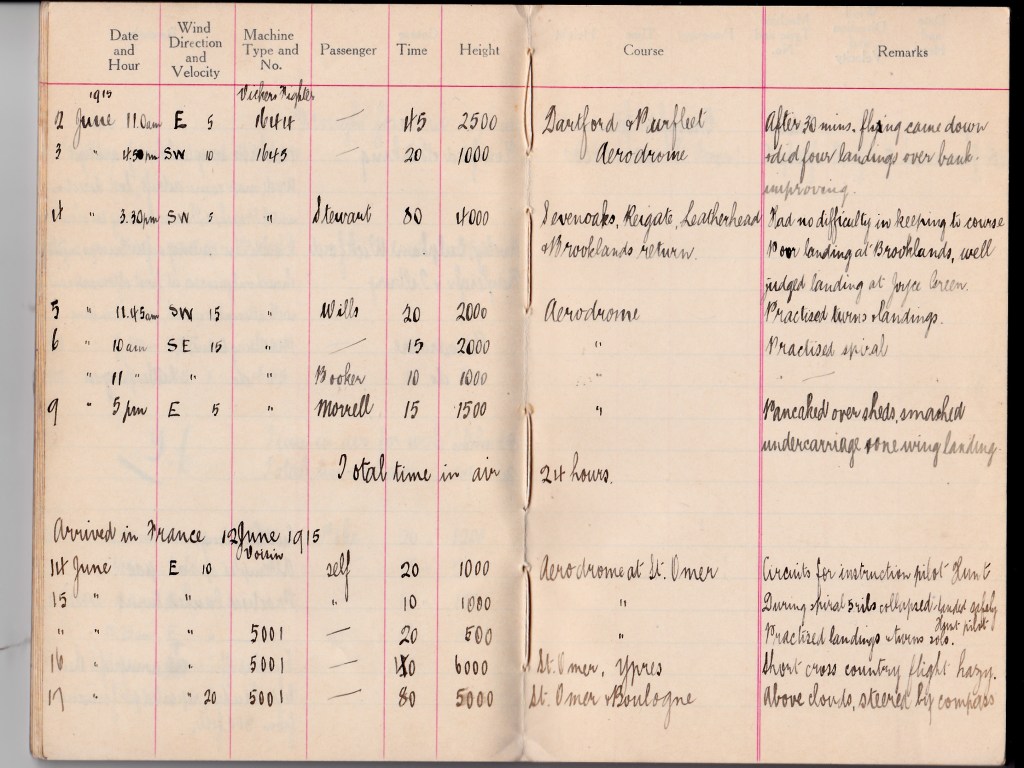

The weather at Estrée Blanche aerodrome worsened in mid-November (1917), and fog made reconnaissance in the whole area extraordinarily difficult. 22 Squadron, still under the command of Major Leonard Learmount, was tasked with finding out what the enemy was up to around German-held Cambrai, information which headquarters badly needed for the planned British assault there on the Hindenburg Line, a heavily fortified German defensive line to the west of the town.

The Cambrai assault, which began on 20 November, was conceived by General Sir Julian Byng as a surprise attack from the west, across terrain suitable for tanks – unlike the Ypres area – and RFC close air support was part of the plan. The latter had proved highly effective toward the end of the Passchendaele battle.

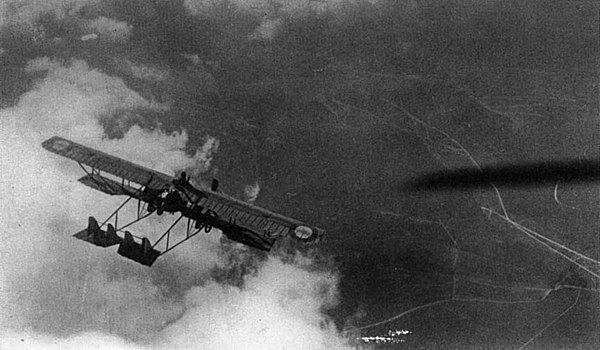

Fog made 22 Sqn’s preparatory reconnaissance sorties dangerous and reduced their effectiveness. Crews transited to the Cambrai area at about 3,000ft, then descended gingerly through the fog as low as they dared, hoping to get sight of the ground and evidence of enemy movements before colliding with church spires or rooftops.

On 20 November the Cambrai offensive began, and yielded a suspiciously successful British six-mile advance over nine days, after which it was brought to a halt. It was still short of the town, but had breached some of the defensive lines. Very quickly, however, the advantage of surprise was lost and the Germans successfully counter-attacked. By the 6th December, they had retaken much of the ground that had been won.

Air Gunner Archie Whitehouse described 22 Sqn’s role at Cambrai: “We had the unenviable job of blowing up the enemy observation balloons, strafing road transport, and making a general nuisance of ourselves. We were down low, flying through our own shell-fire to hammer Cooper bombs on the German anti-tank gun emplacements. We strafed the roads and chased horse-drawn transport all over open fields, and generally played merry hell…

“We fired hundreds of rounds of ammunition and burned out our gun barrels. We returned again and again for fuel, bombs and the reviving encouragement of Major Learmount. Thank God for the Major during those days!”

This, it seems, was about the time when the air gunner and the squadron commander reached an unspoken awareness that they had become the only two remaining aircrew from what Whitehouse called “the Chipilly mob” who were still flying on 22 Sqn. He was referring to the location at which he had joined the squadron about six months ago, in April.

It left them with a feeling of emptiness, against which the only antidote was the adrenaline summoned up by the next sortie. Whitehouse wrote: “We flew, slept, flew, slept and flew some more. We staggered back and forth to our machines, too tired to eat. No-one spoke, no-one laughed, no-one argued. Faces were lined with weariness, pitted with cordite, and daubed with whale-oil.”

Whitehouse described the festive preparations: “We got up a programme that was a honey for wartime humour. Among the mechanics we had a wealth of talent, so we could put on a show worthy of any outfit out there!” They rigged up lights powered from a dynamo lorry and searched out decorations to put up.

Finally, the dinner on Christmas Eve: “The officers, led by Major Learmount, came in and served the Christmas dinner, bundled up in aprons and mess jackets and suitably armed with towels and napkins. We sang and gave cheers for everyone we could think of. There never was such a dinner or so much fun!”

Then they put on the show, with “the inevitable slightly bawdy female impersonator”, tricks, recitations and plenty of songs accompanied by piano. Marie and Annette, waitresses from the small estaminet in the village – and their mother – were guests of honour, along with quite a few other “puzzled-looking” civilians from Estrée Blanche, and they were given seats at the front near the piano. It all ended with God Save the King and the Marseillaise.

Then back to business. C Flight had to go on patrol on Christmas Day, but nothing much came of it. The Hun had chosen to be quiet for Christmas too, apparently.

On 20th January 1918 Archie Whitehouse, whose ambition all along had been pilot training and a Commission, was sent back to England to achieve both, wearing the ribbons for his newly-awarded Military Medal and a chest-full of campaign gongs. He reported in his memoire: “I lived to wear pilot’s wings and fly a single-seater fighter. I lived to see the Armistice!” He clearly felt lucky. He definitely was.

The squadron commander who had bid Whitehouse farewell was now the very last of the aircrew left from January 1917, but he had his work to keep him sane. He still had to lead 22 Squadron’s mechanics, armourers, stores-wallahs, cooks and caterers whose names he knew well, and to encourage the new, barely-trained young pilots and observers to believe in their roles and in their ability to carry them out.

On 22 January 1918 the Squadron moved briefly from Estrée Blanche to Auchel/Lozinghem, then again on 2 February to Treizennes, where losses were high and increasing. The Geman air force was venturing more over the Allied lines than they had been accustomed to do, seeking intelligence for planning purposes. It was on a patrol from Treizennes, on 9 March, in his Bristol Fighter, that Learmount got his blighty while attacking a German aircraft that was being far too successful at directing German fire onto British artillery positions. Although losing blood fast, his remarkable luck still held, and he got his Biff back to base. He was stretchered away from his mount.

From March 1918, No. 22 Squadron found itself dealing with German preparations for the imminent – ostensibly successful but short-lived – Spring Offensive. The German army, commanded by Gen Erich Ludendorff, had benefited from the transfer of huge numbers of troops from the Eastern to the Western Front, and consequently appeared to have assembled the means to mount an attack on a wide front. On 21 March the first of three separate chronologically sequenced attacks took place on different parts of the British sector of the Western Front. Ludendorff’s objective was to drive the British to the Channel coast and cut them off from French forces before the newly-arrived Americans were able to put their full weight behind the Allies.

The final push of the Spring Offensive, in late May, was aimed further south on the French-defended part of the line near the Champagne. But Ludendorff had dissipated his forces too widely and, despite gaining a significant amount of ground, he had failed to defeat the retreating British and French armies, which were able to re-group. By July the attack had ground to a halt without achieving any of its aims. This marked the beginning of a progressive collapse within the exhausted, demoralised German military.

The RFC shipped the badly wounded Learmount back to England, where he was sent to St Bartholomew’s hospital, London, for treatment. France awarded him the Croix de Guerre avec Palme.

At “Bart’s”, Learmount met “Peggy” Ball, a young nursing auxiliary charged with looking after him. Less than two months later – on 7th May – he married her in a church in Muswell Hill, north London, where her parents lived.

While Leonard and Peggy were exchanging vows, the German Spring Offensive was still advancing, but the Allied victory that (we now know) was to come in November was nowhere in sight at that time. Nevertheless, the newlyweds took a few days off to honeymoon at a pub on the banks of the River Thames, at Staines, 15 miles west of London – very rural in those days – and they went rowing together. Wedding photographs show Learmount left the church still using a walking stick.

He was taken off the sick list on 22 August 2018 and posted to No 33 Training Depot Station at Witney near Oxford as an instructor on Bristol Fighters.

Upon his demobilisation in February 1919, Learmount returned to his trading job in the Far East. Once he was established there, his new wife and baby son, travelling by ship (of course), joined him there a few months later.

The marriage lasted a lifetime.

ENDS

Click here to go to Episode One of “Leonard’s War” and read it all again!