(For previous episodes, scroll down)

When Observer/Gunner Archie Whitehouse finally took leave back in England, he found himself feeling restless and directionless, despite giving himself plenty to do. And when leave was over, he was strangely grateful to return to 22 Squadron, now at Boisdinghem, west of Saint-Omer.

But then, as more of his close friends “went west”, he immersed himself in tasks on the aerodrome between sorties “to keep myself from going completely mad”. He did not understand his feelings. “It suddenly dawned on me that the only time I was really content was when I was in the air.”

He talked to – and worked with – the mechanics, the riggers, the armourers, to better understand the machines he worked in and perhaps, by better understanding them, live to tell the tale. He found what solace he could in comradeship, but he had lost so many fellow fliers it felt like a betrayal to make new friends, and he found himself being unaccountably slightly hostile to young aviators just joining the squadron, who looked with admiration at their seniors’ flying brevets and just wanted to learn from them so they, too, could live.

Meanwhile Major Learmount’s wounding in May seemed to have woken somebody at British headquarters in Armentières. He had been awarded the Distinguished Service Order, and the citation for it reveals more about the grind of the RFC’s routine work than a dozen Daily Mirror stories of individual aces’ air-to-air victories. It describes repeated low-level aerial photography sorties by 22 Sqn Fees over the highly fortified Hindenburg Line, which the Germans had been continually engineering since the Somme offensive, and to which they had made a mass strategic withdrawal in March and April 1917.

The carefully planned withdrawal of the Germans to the Hindenburg Line had a significant effect on the course of the war on the Western front. It gave them time to regroup, resupply, and – they hoped – take a break while matters on the Russian front were resolved. They fell back from the Western Front positions to which they had been driven during the Somme battle, and as they went the Germans purposely laid waste to the territory in front of the new, fortified lines, making surprise attack by the Allies even more difficult.

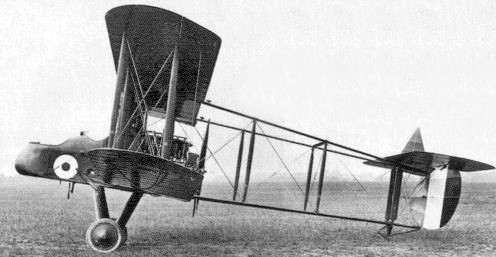

Closely observing activity on the Hindenburg Line was, therefore, important, and 22 Squadron’s “oblique photography” missions were crucial in providing stereoscopic images to the increasingly skilled photography units attached to the squadrons. The sorties were especially dangerous because they had to be flown low and very steadily, about 600ft above the ground. This made the Fees sitting ducks, putting them within range of small arms and machine gun fire from the ground, let alone Archie, and attacks from German fighters. To enable them to do their work without attack from the air, the Fees were escorted by Sopwith Pup fighters of No 54 Squadron flying at a safer height from which they could dive on any attackers.

According to accounts in Peter Hart’s book “Bloody April”, chronicling the period of appalling RFC losses in that month of 1917, Captain BF Crane, a photographic officer attached to 22 Squadron reported on the results obtained on sorties that were mostly led by Major Learmount or Captain Clement: “An average of 2,000 photos daily were being turned over, all from plates exposed by 22 Squadron.”

About two days before the 10th May flight out of Flez on which Learmount was injured, he was flying with a cool-headed young Canadian observer, Lieutenant PHB Ward, whose steady nerve in charge of the camera – aided by Learmount’s rock-steady flying under fire – obtained particularly sharp pictures that converted well to stereoscopic prints, according to Crane, who reported that “about 50 exposures were made and excellent results obtained, the machine returning safely to the aerodrome bearing much evidence of the heavy fire experienced.”

On the 10th May flight – also with Ward – the purpose was to complete a multi-mission photographic task. This was achieved. Ward was killed nine days later on another such mission.

The skies were indifferent to merit and courage.

Part of Learmount’s DSO citation reads: “On nearly all the other occasions on which this officer took oblique photographs, his machine was literally shot to pieces and his escape from injury really miraculous.” It concludes: “This officer as a Squadron Commander sets a splendid example to his Squadron, leading them on patrols, bomb raids and reconnaissances [sic] and instilling in them that fearlessness with which he himself is imbued.”

Tomorrow, Episode 8: No. 22 Squadron receives its new Bristol Fighters, and takes the Germans by surprise. But the crews get new and demanding missions made possible by the Brisfits’ extra performance.