Now called Airport House, this building was one of the world’s first purpose-built air terminals/air traffic control towers. It is on this Croydon site that – until the 1950s – London’s main commercial airport used to be. It now houses a museum full of fascinating artifacts that evoke the exciting – and rather dangerous – adventure that was air travel 100 years ago.

The very first commercial airline flights in Britain – just after the First World War – took place in noisy, uncomfortable aircraft, carrying between two and four passengers in machines converted from their wartime role as bombers.

But toward the 1930s, when Croydon’s new, modern airport terminal was built, things got a lot better, and the glamorous and wealthy flocked to be among the first to fly to Paris in the promised three hours.

Ordinary people could mostly only afford to watch, which they eagerly did from the observation deck on the roof of the terminal, overlooking the grassy aerodrome and watching film stars and royalty walk out to their aircraft.

Everything about aviation then was still so new, so experimental, and the public attended air shows in huge numbers, watching daredevil aviators carry out gravity-defying feats in their flying machines.

The Historic Croydon Airport Trust does an excellent job in bringing all this aviation history to life.

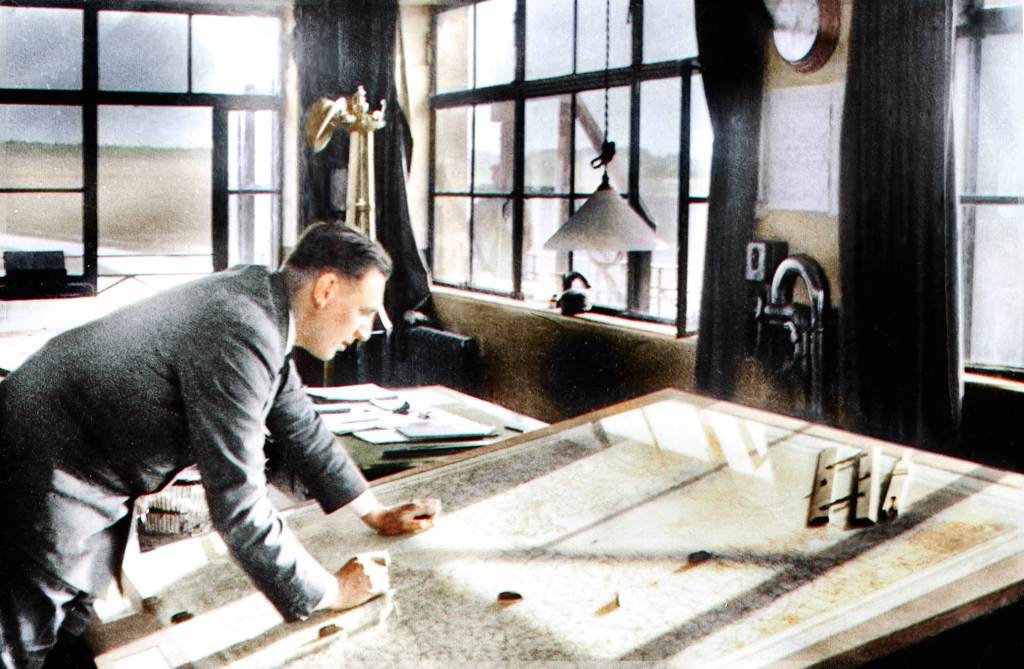

For those curious about how early aviation – and particularly early air traffic control (ATC) – actually worked, this is the place to discover it. As it happens, just a few years ago – in February 2020 – Croydon airport celebrated a century of ATC, because this is the place where it was invented and developed.

Indeed, ATC is something about which even today’s frequent flyers know very little, and learning about its origins – the very basics of early air navigation – will serve to bring to life the essential aspects of modern ATC, because the essentials never change.

In the 1920s the aircraft flew very low by today’s standards – only a couple of thousand feet above ground level. At that height, geographical features like rivers and coastlines, or man-made features like railway lines, could easily be seen if the weather and visibility was good, making navigation by map-reading possible. But if it wasn’t, help from ATC following the advent of radio-direction-finding (see link above to “A century of ATC”) was very welcome to the crews. In marginal visibility, getting lost was quite common, because it was easier than you might think to end up following the wrong railway line!

Pilots now are still expected to do their own navigation, and abide by the rules of the air. ATC’s task is principally to ensure that the flow of air traffic proceeds in an orderly fashion in today’s much busier skies, and that conflicts between aircraft are avoided.

But if pilots do need assistance, ATC is there to help them. Indeed it was at Croydon Airport that the international emergency call “Mayday Mayday Mayday” was first proposed and adopted.