(For earlier episodes, scroll down)

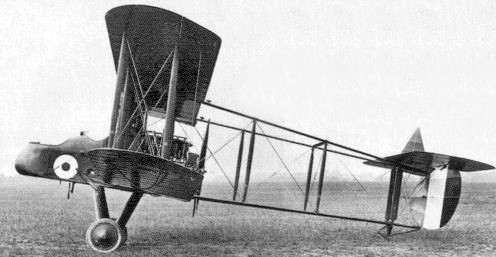

At the beginning of July 1917, 22 Squadron moved to Izel les Hameaux, west of Arras. Its pilots were still flying the FE2bs, but as the month progressed the first of a fleet of F.2B Bristol Fighters began to arrive. These were two-seater strike fighters.

The “Brisfit”, or “Biff”, was not just faster, it was a tractor – rather than a pusher like the Fee, which made it handle very differently. Its armament gave it a formidable field of fire. There was an awful lot for the crews to learn.

The pilots – in the forward cockpit – had a machine gun with interrupter gear, enabling it to fire ahead through the propeller. The observer/gunner’s cockpit, immediately behind the pilot’s, had dual flying controls, and a Lewis gun mounted on a rotating “scarff” ring that gave it a field of fire rearward through a 180deg arc. The Brisfit was powered by a V12 Rolls-Royce Falcon engine, had an airspeed of 126mph (40mph faster than the Fee), a better rate of climb and altitude capability, plus greater range.

Whitehouse caught the buzz that arrived with the new fighter: “From that day on we went to work on Jerry with the Bristol Fighters, and within two weeks the General Staff and royalty were visiting the squadron, and our pictures were being splashed over every paper in the Empire”.

Meanwhile, scanning the pages of Trevor Henshaw’s remarkable gazetteer of RFC experience, “The Sky Their Battlefield”, a change in 22 Squadron’s fortunes is plainly visible in July when the Bristol Fighters began replacing the FE2bs at Izel les Hameaux. The casualties stop for some weeks, and on 29 July 22 Sqn scored its first two F2b air-to-air victories. The Bristol Fighter wasn’t invincible, but its capabilities had taken the Germans by surprise.

One new role enabled by the Bristol Fighters’ longer range was dreaded by the crews. This was operating as an escort for British bombers – de Havilland DH.4s – tasked to fly deep into enemy territory, their bombs targeting the new German airfield at Gontrode, eastern Flanders. From there, German Gotha heavy bombers were known to be taking off every day, aiming for London.

Observer/gunner Archie Whitehouse scripted a particularly lyrical account of a six-ship Brisfit formation taking-off for a Gontrode escort: “They stand throbbing, wing-tip to wing-tip, their propellers glistening in the sunshine. The leader’s hand goes up, and the pilots take the alert with hands on throttles. The leader’s hand goes down and the machines seem to stiffen for the spring as the motors open up. The rudders waggle and the colours flash. The observers in their brown leather helmets snuggle down inside the scarff-ring and flick friendly salutes to each other. Then they are away in a swirl of dust, and suddenly all climb together.”

Once airborne, the Brisfits headed for Ypres, where they rendezvoused with the DH.4s, and set course for Gontrode.

Meanwhile, evident on both sides of the Front were preparations for what became the Third Battle of Ypres, the huge slugging match fought between the end of July and early November 1917, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele. The name of that battle evokes images of men, machines and horses almost immobilised by deep mud , the result of an awful summer of continual, soaking rain and heavy shelling that broke up the ground. Army casualty numbers – on both sides – eventually matched those at Verdun and the Somme.

Casualty numbers at 22 Sqn began to climb as the battle progressed, and as ground commanders looked for new ways of gaining an advantage. During this Third Battle of Ypres, and other peripheral clashes in the area, a new role for air power was being developed: coordinated ground attack, and what would today be called close air support for army units on the ground. Risks were high, because all this work was carried out at low level within the range of ground fire. It included strafing, bombing of enemy airfields, and detailed reconnaissance with rapid reporting back of enemy attempts to regroup or counter-attack.

In early August, 22 Sqn had moved yet again from Izel les Hameaux to Boisdinghem. For the crews, after the relentlessness of flying under fire from above and below, precious off-duty time fostered friendships with the local people that would spawn a lifetime of memories for those few fated to survive – military men and civilians alike. Madame Beaussart’s was an estaminet in a local village, and Marie and Annette who worked there knew the squadron aircraft, their markings and who flew them. Just like the men on the aerodrome, the girls watched the aircraft go, and they counted them back again.

On 19 August, Captain Clement’s Brisfit didn’t return. Clement had stepped in to take a mix of A and B Flight ships out on a mission, because “A” Flight had lost its leader. It was his last sortie. This was awful for the Squadron, and C Flight in particular. Clement’s younger brother Ward Clement had recently joined the Squadron as a gunner, and he and Whitehouse had become firm friends. Clement the younger was distraught and refused to believe Carl wouldn’t return. Hours later he persuaded himself his elder brother had force-landed and would make his way back. But that wasn’t true.

Whitehouse wrote: “When we went back to Madame Beaussart’s, Marie and Annette knew that ‘N’ had not come back, but they said nothing. The coffee and rum were good. I think we drank an awful lot of it.”

After an appallingly wet August, September brought drier weather and good visibility, making the RFC’s close air support in this war-torn region of Flanders highly effective. On 10 September 22 Sqn moved again, out of Boisdinghem to Estrée Blanche. For five days from 20 September 1917, at the Battle of Menin Road Ridge, the 22 Sqn Biffs were used highly effectively for ground attack, air superiority, and reconnaissance. Rapid reporting of German counter-attack manoeuvres allowed Allied artillery to be directed accurately. This clash was one of many on the periphery of the main battle.

On 26 September 1917 Learmount wrote a letter to the HQ of 9 Wing, complaining in detail about how the pilots arriving on 22 from training had not been sufficiently endowed with basic skills like navigation, formation flying and making reliable landings, let alone for air warfare. He named five pilots as an example of what he was complaining about, describing their shortcomings and specific mishaps, usually resulting in significant damage to one of the Bristol Fighters. All were described as having received no training in aerial gunnery, several as having had insufficient experience at cross-country flying (navigation), and most as lacking formation flying skills.

Learmount summed up his problem: “It is at times very difficult to obtain the necessary machines for giving this instruction and although my Squadron may be up to establishment in pilots there are invariably three or four who are not ready for war flying.”

He continued: “Many of my casualties are the result of inexperience and it stands to reason that pilots with no experience cannot put up a decent fight against the pick of the German Flying Corps.”

“I think it is hardly realised at home that the Bristol Fighter is a magnificent fighting machine, and all pilots trained for service on this machine should be of the very best type and should receive far more thorough training.”

Learmount is clearly making a pitch to get the best pilots sent to his squadron! The response arrived from Brigadier General Hugh Trenchard himself, the Officer Commanding the RFC in France, who made it crystal clear that the resources to do more were not available, and that it was the responsibility of the squadron CO to assess the arriving pilots and provide the necessary training that they needed for front line flying. He also emphasised that Learmount’s squadron “gets a fair pick of the pilots that come out from home,” and that 22 could not expect special treatment.

Finally in November came the end of the epic Passchendaele campaign, and the beginning of the Battle of Cambrai. The latter was an attempt by the British to break through the Hindenburg Line for the first time, in a massive attack combining artillery, tanks, infantry and air power.

Tomorrow: Episode 9, in which the winter weather gets very difficult, Cambrai puts new demands on the Squadron, the men put on a Christmas show, Whitehouse goes back to England to train as a pilot, and Major Learmount gets his blighty.