(If you missed the first episode, scroll down to find it before this one)

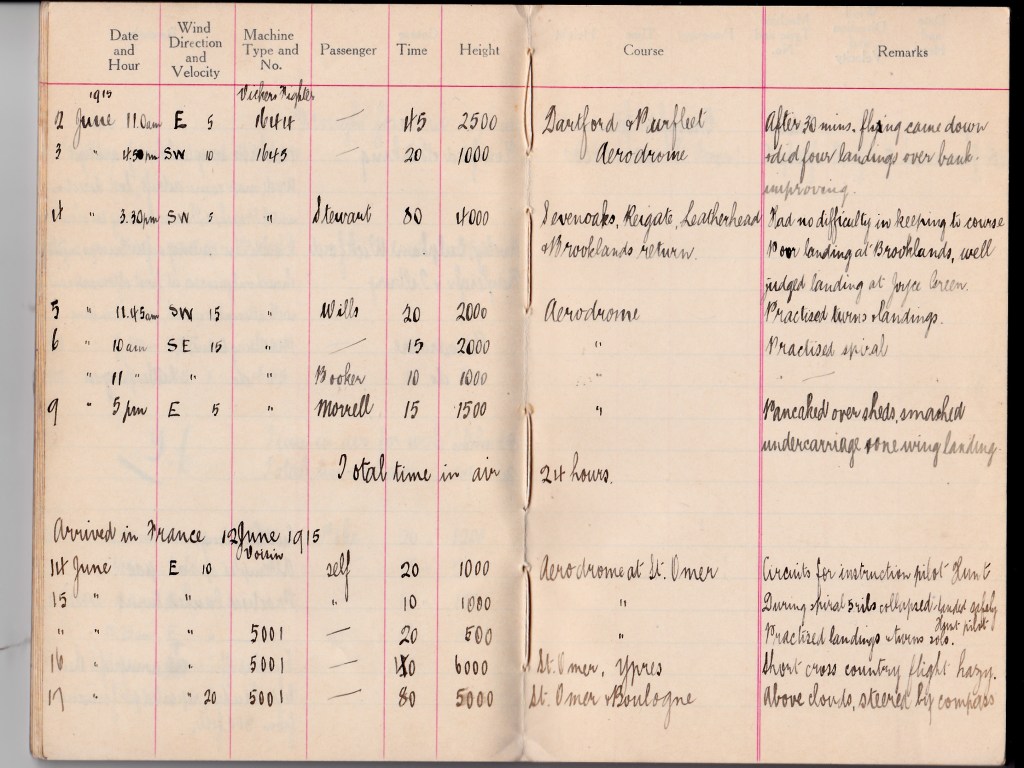

It was on 12 June 1915 – almost the height of summer – that 2nd Lieutenant Leonard Learmount joined his first operational unit – No 7 Squadron – at Saint-Omer aerodrome, north-eastern France. His flying log book records the weather as almost perfect for flying a wood-and-fabric aeroplane: clear with a 10mph easterly breeze.

There is no evidence that Learmount was given an aeroplane to ferry across La Manche to Saint-Omer, so we must assume that – like most men posted to France – he caught the sea shuttle from Southampton to Le Havre and took a boat up the River Seine to Rouen, thence by road to his destination.

Learmount’s flying log book shows that four short trips out of Saint-Omer aerodrome on a new aircraft type were deemed sufficient for him to master its peculiarities and to complete local area familiarisation sorties. The machine he was learning to control was the French-built two-seater Voisin “pusher” biplane [engine and propeller behind the cockpit].

His first sortie consisted of 20min flying circuits, but the second trip was a brief affair lasting 10min. His log book explains: “During spirals, five ribs collapsed. Landed safely.” The instructor had taken control and put the aircraft down without delay.

“Spirals” were climbing or descending turns, and if the aircraft was not kept in balance by a careful combination of aileron, rudder and elevator, a spin could develop. The Voisin had a level airspeed of about 65mph, but that was only about 40mph above its stalling speed. The evidence suggests that, before the need for a formal flying training syllabus was recognised in 1916, military aviation was seen simply as a means of putting eyes in the sky for the army, and – especially at first – there was no preparation for air-to-air combat. The pilots were just seen as drivers, their task being to fly cautiously and avoid loss-of-control so as to bring their observers home safely to pass on their vital reconnaissance information.

After his final familiarisation sortie, Learmount wrote in his log book: “Above clouds, steered by compass.” He had clearly experienced neither of those things before, yet he was deemed ready for command of a two-seater aircraft operating in hostile skies above the battlefield.

The very first RFC air-to-air combat losses were reported in early June 1915. Indeed a 7 Sqn RE5 was “shot-up” and damaged at 7,000ft over Douai/Valenciennes on 6 June, and on 6 July 2nd Lieutenants LW Yule (pilot) and RH Peck (observer) in a Voisin were both wounded by “exploding cartridges” at 7,000ft near Armentiéres. Both crews successfully recovered to Saint-Omer. (Combat detail from Trevor Henshaw’s admirable “The Sky Their Battlefield”)

Air warfare tactics in that precise location not far east of Ypres were evolving, but were about to start developing at breakneck speed. Air-to-air combat was still very rare, many of the crews armed only with rifles and revolvers, and the primary mission was still reconnaissance and artillery spotting.

In Learmount’s early operational flying with 7 Sqn, he flew the painfully slow Voisin first out of Saint-Omer, and then from other aerodromes further east in the “Ypres Salient” region of Flanders, among them Droglandt. At first, he was purely carrying out reconnaissance and artillery-spotting for the army, but the Voisin was equipped with a Lewis light machine gun, so it was capable of defending itself.

Flying with Learmount on his first operational sortie in command – on 19 June 1915 – was his observer/gunner, the same 2nd Lieutenant Peck just mentioned earlier. Indeed Peck almost certainly directed his rookie commander’s sortie! His handwritten reconnaissance report (see below) records the aircraft’s take-off from Saint-Omer at dawn (04:30), and describes observed activity behind enemy lines between Courtrai and Ghent, Flanders. The pencilled words, inscribed carefully by cold hands, provide details of train and other surface transport movements, assemblies of troops and equipment and estimated numbers. The aircraft landed at 07:45am, so they had been airborne for 3h 15min.

On the ground, beneath 7 Sqn’s patrolling aircraft, a fierce German offensive was raging against the British forces holding Ypres. The airmen, pre-briefed on what the army wanted them to look out for, provided their recce reports direct to specific units on the ground. The German offensive was eventually stalled, but at huge cost to both sides.

In a 31 July 1915 combat report filed by Learmount’s observer/gunner describing an inconclusive encounter with an enemy biplane, the Voisin crew’s armament was recorded as: “Lewis gun, rifle and pistol”. The observer, 2nd Lieutenant HH Watkins, initiated the hostile exchange with his Lewis gun, but the German machine positioned itself behind the RFC aircraft. Watkins reports: “I fired over the top plane with the pistol, and the enemy immediately turned and disappeared to the east.” The German aircraft was not identified by type, but was described thus: “Tractor biplane with covered-in fuselage. Machine gun firing to rear. Speed about 85mph.” This kind of encounter was common at that stage of the war, but exchanges quickly became more dramatic as Germany started to field armed fighters.

Meanwhile 7 Sqn aircraft were increasingly often engaged in air-to-air exchanges and, with the arrival of August, the “Fokker scourge” began to take its toll of RFC aircraft and crews. The Fokker Eindecker was, as its name implies, a monoplane, and it was a “tractor” (engine and propeller at the front), not a “pusher”. It was the first aircraft on either side to be armed with a forward-firing machine gun equipped with interrupter gear to enable it to fire ahead through the propeller. This made it a game-changer, and accelerated the development of air combat tactics.

The Eindecker’s armament might have caused far more problems than it did, but fortunately for the RFC the aircraft had an unreliable engine, and was difficult to fly, causing many training crashes. Thus only a small number were effectively deployable on a daily basis at front-line units. In fact it was so difficult to manage that the Germans took the Eindecker out of service in early September, but such was its known effectiveness in capable hands that it was declared operational again a few weeks later.

And the RFC’s airborne operations were becoming more varied. By early autumn, bombing sorties were more regularly executed – including against German aerodromes. For example a handwritten, undated operation order held by the UK National Records Office tasked five 7 Sqn pilots – including Learmount – with carrying out two bombing raids on Gits aerodrome in Flanders, near the Gits railway station just east of the Torhout-Roulers road. The first was to be at 7am, the second at 2pm to disrupt attempts at repair. Each aircraft normally carried two or three 20-pound bombs.

There was a difference between the overall aviation strategies of the Allies and Germany. Germany frequently had technology and performance advantages, but they had a significantly smaller aircraft fleet and knew it. The RFC leadership, notably the general commander of the RFC in France Colonel Hugh Trenchard, wanted the RFC crews to fly aggressively – whether trained for combat manoeuvres or not – and venture every mission into airspace over the German lines to gain intelligence and disrupt operations. The Germans, on the other hand, would work to limit their own losses by staying defensively over their lines, except for making brief, organised formation attacks to the west of the Front.

When the Battle of Loos began on 25 September 1915, No. 7 Sqn was flying out of Droglandt, 20km west of Ypres in Flanders, heavily involved in providing air support, bombing and reconnaissance for the allied troops, operating a mix of BE2c and RE5 aircraft. The Battle of Loos was a British offensive on the Western Front close to Lille, not far north of Arras which included the first British use of chlorine gas on the ground. But by 8 October the push came to a standstill against staunch German defences.

Learmount himself was now mostly flying the BE2c out of Droglandt. The BE2 series had originally been designed – in 1912 – as a very stable, unarmed reconnaissance machine, and that was fine until the Germans introduced well-armed aircraft like the Fokker Eindecker. The Allies didn’t have an answer to the latter’s capabilities until early 1916, so the BE2c’s previously desirable stability made it a sitting duck (more about this in future episodes). Many were shot down but – fortunately – because they were such stable machines to handle, the crews were often able to control the damaged machine to a forced landing.

So many BE2cs had been built, however, that they continued to be used for reconnaissance and bombing into 1917, and crews began to dread being assigned to them.

Meanwhile Learmount was recommended for a Military Cross. The citation lauded his general performance since joining 7 Sqn in June, but it described a specific action on the second day of the Battle of Loos: “Consistent good work, done most gallantly and conscientiously from 13.6.15 to present time. This Officer bombed and hit one half of a train on 26.9.15, coming down to 500ft immediately after Lieut DAC Symington had bombed the other half.” The train was on the Lille-Valencienne line, and Symington had achieved a direct hit on it close to its front, bringing the whole train to a halt. Just after that, Learmount dropped a 100lb bomb that made a direct hit on one of the coaches in the train’s centre.

The point about coming down to 500ft or less is that it puts the aircraft within easy range of machine gun fire, and trains were almost always armed.

Tomorrow: Episode 3, Learmount is seconded to the French Armée de l’Air to report on their development of night bombing techniques