(for preceding episodes, scroll down)

In early March 1916, 2nd Lieutenant Leonard Learmount was seconded from his unit, No. 7 Squadron, to the French Bombardment Group at Malzeville, close to Nancy and not far from the France/Germany border in embattled Alsace-Lorraine. His task was to observe bombing techniques – particularly night bombing – and to write a report for the RFC.

Selection for this duty suggests he was being prepared for command despite the brevity of experience gained in the twelve months since he had enlisted.

Here are some extracts from Learmount’s Malzeville report:

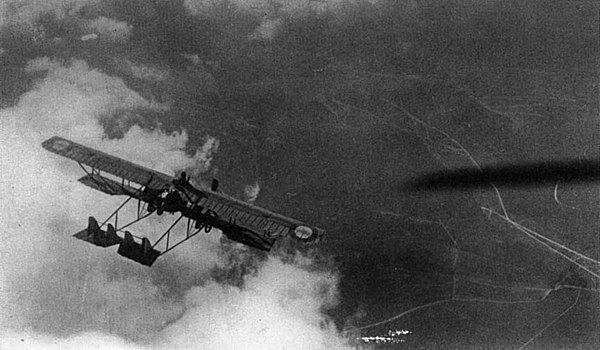

“There are 5 squadrons stationed here, each containing 10 machines. Most of these are Voisins, and the rest double-engine Caudrons. The Voisins will shortly be entirely replaced by Caudrons. These squadrons do not work other than bomb dropping, and one of them is kept entirely for night flying, the pilots being trained exclusively for this purpose.

“The Voisins carry 10 bombs of 10 kilos inside the nacelle. They are placed in an upright position, 5 on either side, and the opening of slides permits the bombs to fall. The Caudron carried five 20-kilo bombs under the nacelle with a release similar to our own.”

Night bombardment

Learmount’s report about night bombing operations reveals a tentative, experimental approach by the French Armée de l’Air to this new type of operation.

“The most elaborate arrangements are made for flying by night, each machine carrying a red and blue light on the wing tips., and three powerful electric lights under the nacelle which can be made to face in any direction. The lighting Is obtained from an accumulator which is charged by a small dynamo driven by a fan fitted to the lower plane.

“There are searchlights at intervals of about 20 yards trained onto the aerodrome, and 3 or 4 forming a crescent round the aerodrome, which point into the air and guide the machines back.

“Machines bombard at night time in groups of 4, and before leaving the aerodrome they signal by means of their electric lights that they are starting, or, if the engine is running badly, they signal that they are going to land. All signals are repeated from the ground by a searchlight to show the machines that their message had been received. When the lines are reached, all lights are extinguished.”

Night navigation was basic: “Machines always fly up the right-hand side of the river, returning on the opposite side.” The report does not name the river or rivers, but Nancy is near the confluence of the Moselle, Meurthe and Marne. “Only towns or points near a river are bombarded at night time, and the machines only fly when the night is clear. When the first man arrives at the objective, he drops incendiary bombs, so that, in the event of all lights being extinguished, the next three can see their objective. The first man in the second group drops incendiary bombs in the same manner.

“Machines fly at about 6,000ft and are never attacked by hostile machines, and have never been damaged by anti-aircraft fire. The French artillery and infantry in the area which the machines fly over are always warned that a raid is taking place, so that they do not put searchlights on their own machines.” Daytime bombing raids, the report says, aim for munitions factories, and railway stations or junctions, so at night the implication is that any of these close to the river they followed for navigation are fair game.

The night bombing tactics clearly left the Germans at a loss as to how to respond. It seems at night they could not identify the machines nor precisely where they came from. “German machines seldom visit the aerodrome and never drop bombs in this district in any quantity. The aerodrome is protected by anti-aircraft guns and patrolled by Nieuport machines. The Nieuport is kept entirely for fighting, and the squadrons composed of these are stationed at Bar-le-Duc.”

Learmount added a personal postscript to the report: “I was very struck by the cheerfulness and confidence of all the French Officers and troops with whom I came into contact. The utmost confidence prevails with regard to the result of the battle around Verdun.”

Verdun was not far north-west of Nancy, and the battle of that name turned out to be the longest and most bloody single campaign of the Great War. Between its inception on 21 February and end on 18 December 1916, the French lost 400,000 men and the Germans 350,000. By Christmas 1916 it was apparent that the dogged French defence had prevailed.

In the light of history, it is instructive to see Learmount’s observations on French army morale, recorded at Malzeville, during the first two weeks of the Battle of Verdun. Despite being a very junior allied officer, he clearly knew that repelling the German push at Verdun was vital, and was also aware that the conflict was quickly developing into a particularly nasty encounter. “I understand that up to the time I left, no general reserves had been called upon, and only the Reserves of the Divisions involved being in action. I saw many troops travelling up to the firing line, and it was remarkable the cheerful way in which the men sang and joked among themselves. One or two occasions when I was noticed the men all called out Anglais, Anglais and cheered, shewing the greatest friendliness.” Learmount was witnessing to the fact that, contrary to established British folklore, sang froid – and cheerfulness too – wasn’t a uniquely British reaction to wartime adversity.

He added: “In conclusion I should like to say how hospitably I was treated by the French Officers. A car was placed at my disposal, and each day I was invited to lunch or dine with either the Commandant or the Officers. When dining with the latter I thought it remarkable that every officer at table had one, and in many cases, two medals, and when I questioned them about this, I was told that the reason was these medals had been given to them previous to joining the Flying Corps, and it was largely owing to their meritorious service that they had been chosen.”

Learmount’s report was dated 11 March 1916.

Tomorrow’s episode 4: Learmount is given command of No. 15 (Reserve) Squadron, an aircrew training unit at Doncaster, south Yorkshire. Although he had only 11 months of operational flying himself, his task was to supplement the basic flying training of new pilots with some rudimentary mission skills before posting to France, where they would arrive just in time to provide air support for the massive Somme offensive. Meanwhile he’s ordered by the authorities to write an article for the Daily Mirror to provide the British public with a picture of what it’s like to be a military aviator.