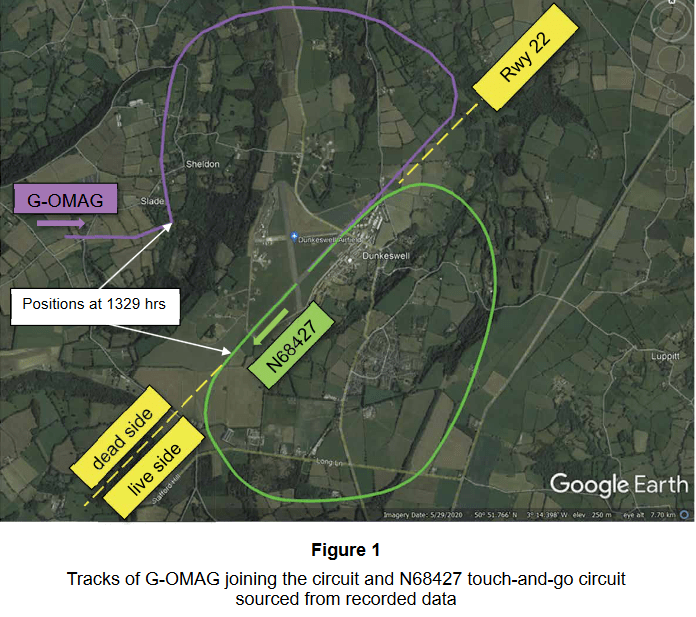

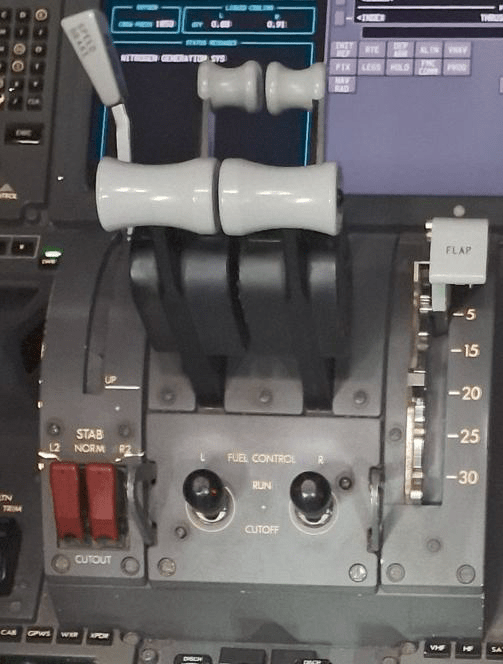

The movement of two small switches on the aft end of the flight deck centre console, reachable easily by both pilots, appears to hold the key to what happened to the Air India Boeing 787-8 that crashed fatally just after take-off at Ahmedabad on 12 June.

It seems that one of the pilots selected these switches from “Run” to “Cut Off”, stopping the engines at a critical point just after the aircraft became airborne. The purpose of this article is to examine the arguments for and against deliberate action (compared with unintentional error) on the part of one of the Air India pilots.

On 11 July the Indian Air Accident Investigation Bureau published its preliminary factual report on Air India Flight AI171, a Boeing 787-8 registration VT-ANB. This has revealed the movement of the fuel control switches (FCS) mentioned above, and the resulting consequences of that movement. The data confirming this was derived from the two Enhanced Airborne Flight Recorders (EAFR) in the accident aircraft.

There are two FCSs, one for each engine in a 787. They have two settings: Cut Off and Run. The first act by any crew in starting a 787’s engines on the ground is to set the switches to Run. On the ground or in the air, setting the switches to Cut Off stops the fuel flow to the engines. (See photograph below, showing the switches just behind and below the engine power levers)

According to the AAIB report, just after take-off at Ahmedabad, these switches were moved from Run (up position) to Cut Off (down position). The left switch was moved first then, one second later, the right switch. This action cut off the fuel flow to both engines. There is no automatic function that could move these switches, so they must have been moved manually, or by something physically impacting them. Each switch has a locking mechanism so it cannot be moved accidentally, and there are guard brackets either side of the pair to deflect inadvertent contact by objects. To select the switches from one setting to the other, they must first be pulled out against a spring force to release a locking mechanism, then moved up or down.

Timeline (UTC):

08:07:37 VT-ANB begins take-off roll. 08:08:39 Lift-off at 155kt. 08:08:42 Max airspeed achieved 180kt, also No. 1 FCS switch was moved from Run to Cut Off, followed by the FCS for engine No. 2. 08:08:47 the Ram Air Turbine began supplying hydraulic power. 08:08:52 No 1 engine FCS moved from Cut Off to Run. 08:08:56 No 2 engine FCS moved from Cut Off to Run. 08:09:05 Mayday call transmitted. 08:09:11 EAFR recording stopped.

The report says: “In the cockpit voice recording, one of the pilots is heard asking the other why did he cutoff [sic]. The other pilot responded that he did not do so.” Each pilot is recorded on a separate channel, so the AAIB must know which pilot made each statement, but has decided not to release the information at this preliminary stage, The report confirms that the copilot was the pilot flying, the captain the pilot monitoring. So it seems that one of them, apparently, moved both FCS from Run to Cut Off (see Timeline above), and the other noticed him doing it. Then, about 10 seconds later, one of the pilots attempted to restart the engines by restoring both FCSs to Run.

The report explains the effect of restoring the FCSs to Run, first in 787s generally, then specifically what happened in this case: “When fuel control switches are moved from CUTOFF to RUN while the aircraft is inflight, each engines full authority dual engine control (FADEC) automatically manages a relight and thrust recovery sequence of ignition and fuel introduction. The EGT [exhaust gas temperature in VT-ANB] was observed to be rising for both engines indicating relight. Engine 1’s core deceleration stopped, reversed and started to progress to recovery. Engine 2 was able to relight but could not arrest core speed deceleration and re-introduced fuel repeatedly to increase core speed acceleration and recovery. The EAFR recording stopped at 08:09:11 UTC.”

Take-off and early climb is a period of intense concentration by both pilots, the joint task being to ensure the aircraft maintains a steady climb while allowing the airspeed to increase gradually in a controlled way.

Under normal circumstances, after unstick there is only one actionable task for the pilots to carry out quickly: to check that a positive rate of climb is confirmed by the flight instruments, then select the undercarriage up. This task is normally carried out by the pilot monitoring on orders from the pilot flying, and it would entail moving the undercarriage control lever – located on the forward instrument panel – manually upward. In this case, according to the report, no-one called for the gear to be retracted, and no-one selected it up.

Instead, at about the time the gear would normally have been retracted, the FCS were moved downward from Run to Cut Off, the left switch first, the right switch a second later.

It is difficult to imagine that a crew member would have made such a gross error as reaching down and slightly back to move two small switches downward, one after the other, as a substitute action for a well established routine which would have involved reaching forward to move a single lever upward. And there was no cueing request from the pilot flying to pull the gear up anyway.

Pilots have occasionally, however, carried out inadvertent gross errors that almost defy credibility. You can see here the description of how, in January 2023, a Yeti Airlines ATR72 scheduled passenger flight was inadvertently set up for disaster during a visual circling approach to land at Pokhara airport, Nepal. I wrote that linked piece based on the preliminary report, but when the final report was published by the Nepal authorities it gave the following verdict: “The most probable cause of the accident is determined to be the inadvertent movement of both condition levers to the feathered position in flight, which resulted in feathering of both propellers and subsequent loss of thrust, leading to an aerodynamic stall and collision with terrain.” The check pilot had been asked by the pilot flying to increase the flap setting from 15deg to 30deg, but instead of moving the flap lever, he moved the pair of engine condition levers (picture supplied in linked article) to the position that demands the propellers to feather and stop turning.

If one of the pilots of AI171 did know what he was doing when he moved the FCS, he must have known that his action would have more or less guaranteed the result the world has witnessed, because there was insufficient time to restore usable power once it had been cut. VT-ANB was airborne only 3 seconds before the first FCS was switched to Cut Off, followed a second later by the second FCS, then ten seconds after that the FCS were both switched back to Run. The total airborne time was 42 seconds before colliding with the buildings that began break-up of the aircraft.

As for the likelihood that professional pilots would want to cause the destruction of the aeroplane they are flying, history provides evidence that it happens from time to time.

This was the summary of the situation as presented in the FlightGlobal annual safety review for calendar year 2023, which points out that deliberate acts by pilots to bring down airliners have been carried out by aircrew from all regions and cultures: “Pilot suicide on commercial flights in the last three decades has not involved only Europeans and North Americans. A Japanese, a Moroccan, an Egyptian, a Mozambican, a Botswanan, and a Singaporean, among others, have all been involved. The Flight Safety Foundation’s Aviation Safety Network accident database shows that, in its records beginning the 1950s, there has been a marked acceleration in the numbers of flights brought down by pilot suicide since the beginning of the 1990s, and this acceleration has continued in the new century. It is undoubtedly a modern flight safety hazard.” Since that time, although China has not confirmed it, the rest of the world has reason to believe that the March 2022 loss of a China Eastern Airlines Boeing 737 was not an accident.

It is inevitable that deliberate action by flight crew should be considered when a disaster like AI171 occurs. The India Air Accident Investigation Bureau will undoubtely investigate this possibility. But just one part of the trajedy is that, when all the flight crew die, their intentions will never be known for certain.