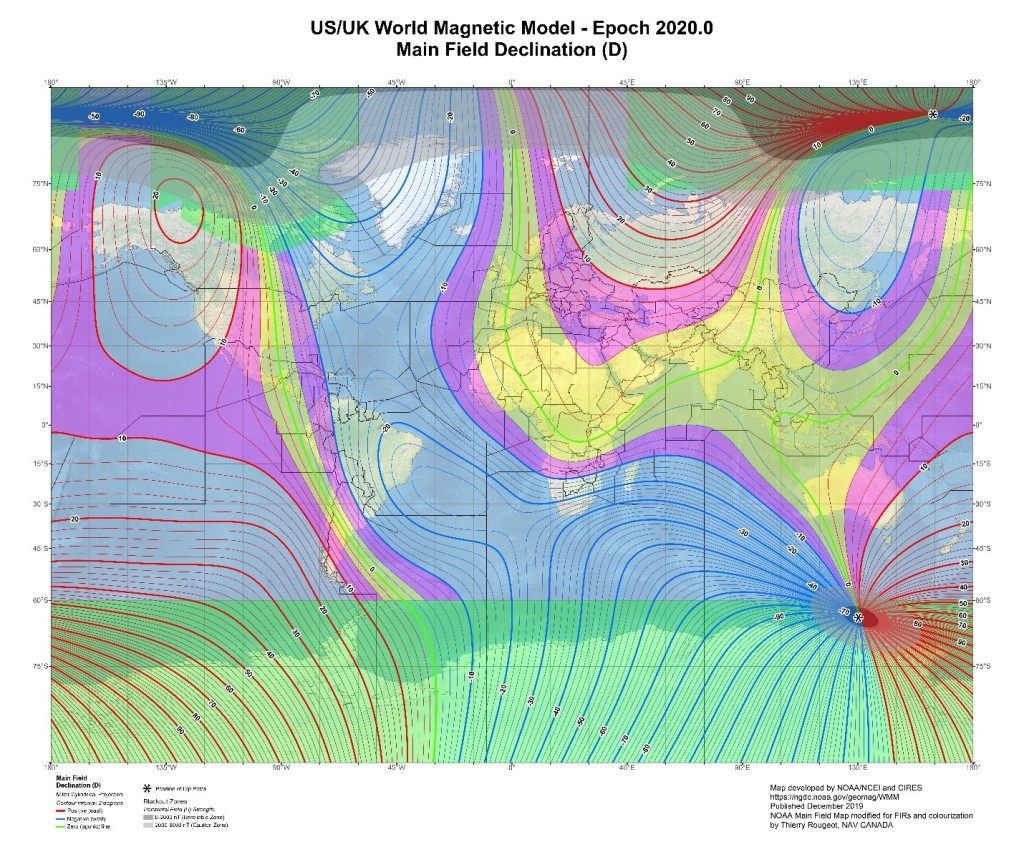

Results of the ongoing study into how aviation should carry out a transition from using Magnetic North as its navigation heading reference to True North may soon be pre-empted by a geomagnetic cataclysm.

If that sounds a little over-dramatic, it isn’t.

Evidence suggests the chance of a polar reversal of Earth’s magnetic field – a phenomenon known to have happened many millennia ago – may be particularly high right now. But the truth is, no-one knows for sure.

What is known is that, since 1990, the previously gentle migration of Earth’s North Magnetic Pole across the Arctic region of north-eastern Canada has accelerated significantly. Such an acceleration has not been recorded before, so whether this is a precursor to a magnetic polar “flip” is simply not known.

Meanwhile the Polytechnic University of Bucharest’s Faculty of Aerospace Engineering – an observer at the Attitude and Heading Reference Transition Action Group (AHRTAG) – has decided this possibility needs to be investigated, if only to come up with a case study to determine what the world’s navigators would have to do if the “flip” happens before the aviation industry transitions to navigation by True North.

The tentative date for that changeover is 2030. The marine industry is insulated against this problem because it transitioned to navigation by True North in the early 1970s.

Bucharest’s studies so far indicate that a polar reversal, according to geological data about a previous such event, could take place over a period of about 100 years, the poles tipping at a rate of about 3deg per year. Such a rapid polar migration would make the continuing use of the earth’s magnetic field as a heading reference totally impractical.

But no-one knows for sure whether the next “flip” will take as long as 100 years.

With this possibility in mind, it is tempting to re-orientate the studies of bodies like AHRTAG (a working group of the International Association of Institutes of Navigation) – so they move away from persuasion backed by data, and move toward simply agreeing the methodology for a transition to True as soon as possible.

But the plan right now is to continue persuading all the global players – airlines, aircraft manufacturers, avionics manufacturers, airports, air navigation service providers and aviation authorities – to come voluntarily on the journey to the “Mag2True” transition. After all, Bucharest University has not reported – yet – on its polar reversal case study!

Apart from potentially confounding aviators, no-one knows what the terrestrial effects of a magnetic polar reversal could be. Will all seasonally migrating animals, birds and fish be similarly confounded? We don’t know.

Above: a gathering of some of AHRTAG’s members meeting on 5 June at the Royal Institute of Navigation, London, England. At the head of the table on the left is Susan Cheng of Boeing, and to the right is Anthony MacKay of Nav Canada, AHRTAG’s chairman.