Research I have been conducting into my grandfather’s Royal Flying Corps/RAF service in the Great War (1914-1918) has yielded unexpected detail about basic flying training for pilots in those early days. Or, more accurately, the lack of it.

When I began the research task – some three years ago – I was focusing on WW1 front line operational flying techniques. But it gradually dawned on me – as a former RAF Qualified Flying Instructor – that very little – even now – has been written about initial pilot training in 1914 and 1915.

Just consider the training context at that time. The Wright brothers first flew in 1903, so in 1914 aviation was still in its infancy.

When mankind first ventured into the sky he didn’t know what he would find, nor how to deal with it. You cannot select “the best” prospective pilots when you don’t yet know what skills or aptitudes aviators need, nor even how to recognise them when they are present in a candidate.

Indeed, the army and navy leaders in 1914 had only a rough idea of how aeroplanes might best be employed in the military context. So, beyond the obvious need to inculcate in pilots whatever magic skills are required to get the aircraft airborne and keep it there, they didn’t have a clear idea of what mission skills the crew might need, nor how best to teach them.

Right from the start, soldiers and mariners definitely knew that the ability to see over the horizon – or even over the nearby hill – would be highly desirable, and a bird’s-eye view would enable the aviators to identify and observe enemy positions and logistical preparations, then report back to surface units.

Air-to-air combat skills did not even begin to become an issue until mid-1915, because most of the aircraft in use at that time had originally been designed as unarmed reconnaissance machines.

In order to appreciate fully why pilot training was so primitive in 1914 and 1915, it is essential for researchers to remind themselves constantly how primitive the technology was, and how little the practitioners knew about aviating. In the RFC there were no trained instructors and no formal flying training syllabus until late in 1916. Learning to fly was an exercise in trial-and-error. To learn more, you had to survive each sortie.

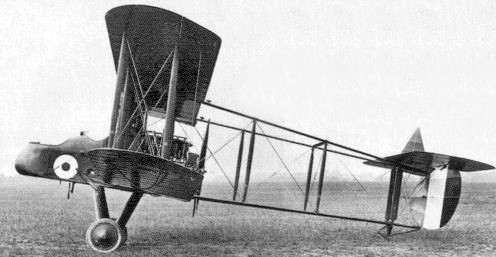

Maurice Farman Longhorn, a training machine in 1915

Estimates of the number of pilot and observer deaths in the Great War have been set as high as 14,000, with 8,000 of them occurring during training. More recent studies, combining fatalities, missing, shot down, and captured suggest 9,000 is closer to the mark for the total, and the number of specific training casualties is uncertain – but it was staggeringly high by today’s standards. A young American aviator training with the RFC at its Montrose, Scotland training base in 1913 wrote home that “there is a crash every day and a funeral every week.” And that was just on his base.

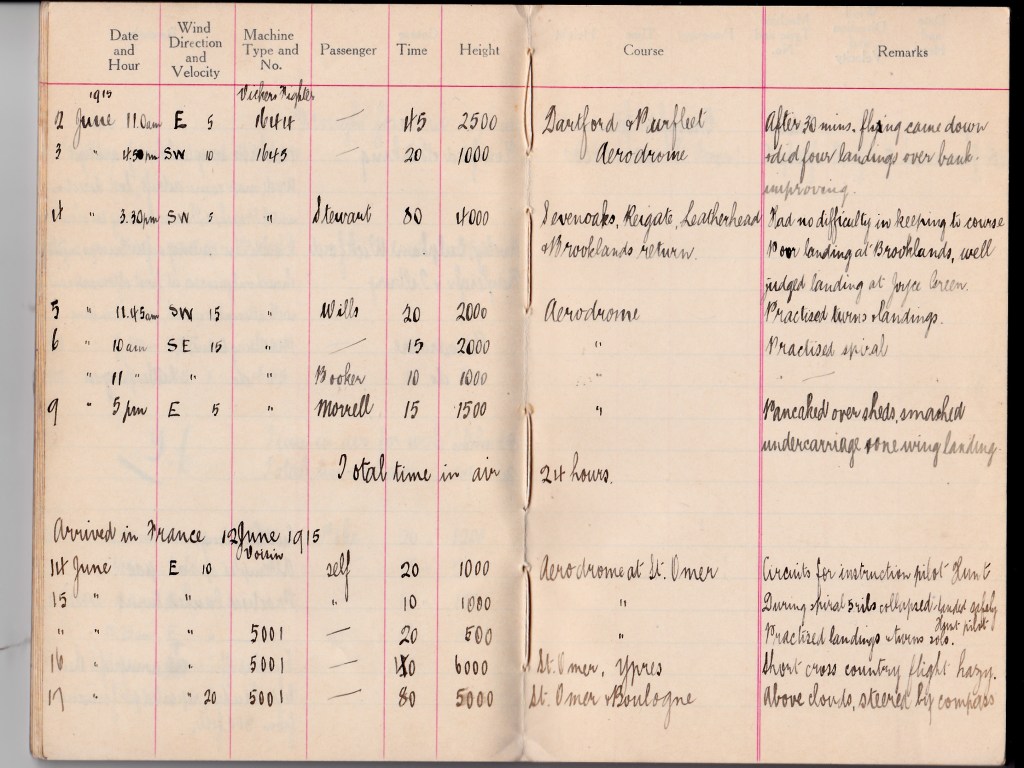

At the end of my grandfather’s training course in June 1915, his flying log book recorded exactly 24 hours airborne time. To train for a private pilots licence today you would need 35 hours or more to gain the necessary skills to satisfy the examiner, and today’s aeroplanes are far more reliable and much easier to fly.

In the remarks column against the entry for Learmount’s last training flight at Brooklands aerodrome, Surrey, on 9 June, he wrote the following: “Pancaked over sheds, smashed undercarriage and one wing landing.” That was clearly good enough for the RFC, because three days later he joined No 7 Squadron at Saint-Omer in France “ready” to fly and survive in the hostile skies over the Western Front.

Evidence abounds that, until mid-1916, young aviators were sent to the front-line squadrons with the basic ability to get airborne, fly cautiously, and recover safely to their base aerodrome. The pilots were little more than drivers for the observer/gunners who would gather the intelligence the army needed. Mission training took place “on the job”. Pilots who survived multiple sorties, possibly by luck, acquired additional skills and knowledge by default, but almost certainly picked up many bad habits and misconceptions too.

Major Raymond Smith-Barry – a graduate of the very first course at the Central Flying School, Upavon in 1912 – and today credited with being the founder of modern aircrew training standards in the RAF – had served as an RFC pilot in France from August 1914. By 1916 he realised that the standard of flying among the arriving aviators was simply appalling, and he decided something had to be done. By late 1916 he had compiled a formal pilot training syllabus, which he first introduced at Grange airfield, Gosport, on England’s south coast near Portsmouth, where he was appointed Commanding Officer of No 1 (Reserve) Squadron – a training unit – and took up his appointment there in December 1916.

Smith-Barry also invented the Gosport Tube, a tube through which the instructor could speak to the student, which was widely fitted to training aircraft from June 1917 onward. The new flying training syllabus, plus the improved instructor communication, benefited training hugely.

Smith-Barry was clearly not the only RFC aviator who had noticed how inadequately trained the young arrivals in France were because, by mid-1916, some training bases back home were beginning to provide basic mission training for pilots who had completed their primary flying tuition. 2nd Lieutenant LW Learmount, my grandfather, who had only graduated from his primary training a year earlier, was made commanding officer of a training unit, No 15 (Reserve) Squadron, at Doncaster, South Yorkshire, in May 1916. Within days he was promoted to Lieutenant, then Acting Captain, to provide him with the authority to carry out the task.

There was clearly a realisation by then that German machines were getting faster and better armed, and that pilots were not only going to have to be drivers, but fighters and also bombers. Smith-Barry’s controversial (at first) insistence that pilots should be trained to fly their aeroplanes to the very edges of their flight envelope, and to recover successfully if they strayed outside it, was gaining ground.

Fast-forward a year or so to September 1917, and by that time Learmount – now an Acting Major – had been the commander of No 22 Squadron for about 9 months, flying Bristol Fighters over the Western Front in France, and he made it clear that he was not happy with the skills of the pilots arriving on his unit. He complained in a letter to HQ 9 Group that arriving pilots had no training in aerial gunnery, formation flying and navigation.

The written response – almost a rebuke – came direct from Brigadier General Hugh Trenchard, Officer Commanding the RFC in France, who made it crystal clear to Learmount that that the resources to do more were simply not available, and that he considered it the squadron commander’s task to bring the skills of his new pilots up to standard where they were found lacking.

You can find much more in my nine-part serial “Leonard’s War”, which traces Learmount’s path through the RFC/RAF from training in 1915 to demob in 1919. For any of you who have read it before, since then it has been considerably expanded and edited as new historic material has come to light, and it remains a work in progress to this day!