For more than 50 years Flight International/FlightGlobal has been publishing a review of world airline safety performance annually, but for the last 45 of them I have been the compiler and author. The most recent review – containing analysis and a list of all the fatal and many of the significant non-fatal airline accidents in 2025 – can be found here on FlightGlobal’s website.

My first safety review for Flight International magazine covered the year 1980. A few years later, in 1985, I reported on the worst year in aviation history in terms of the number of passengers and crew killed: 2,230 deaths in 41 fatal accidents. Last year the figures were respectively 420 and 11, despite the fact that the number of airline passengers carried is now about four times what it was in 1980, and the number of flights has increased about three-fold.

So where are we today in terms of airline safety performance? Obviously massively better than it was in the 1980s, but by comparison with the annual figures in the most recent decade, 2025’s numbers were slightly lower than the average for fatal accidents, and rather higher than the average (276) for the number of annual fatalities.

FlightGlobal/Flight International explains: “The principal reason for the relatively high casualty numbers – a total of 420 for the year – was that more than half of them died in a single, catastrophic crash involving an Air India Boeing 787-8 after departing Ahmedabad International airport on 12 June.”

Flight concedes, however, that “2025 was an unremarkable year – statistically – for fatal accidents.” And those most recent ten-year figures have been remaining fairly constant around a historic best-ever level, so any useful safety review needs to ask what the industry is getting right, as well as studying the mistakes.

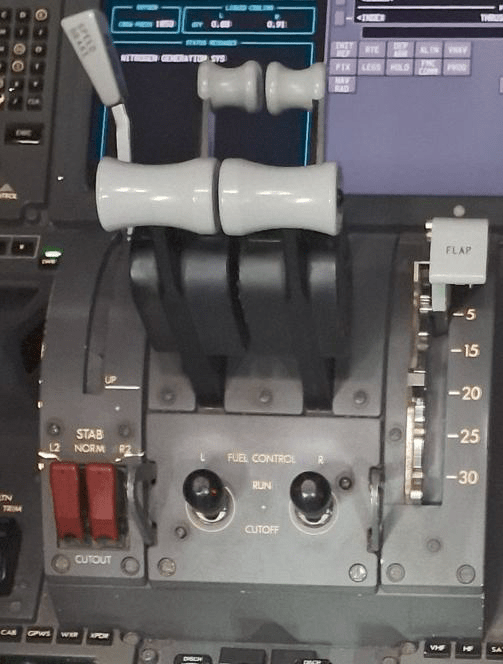

The article debates in detail whether the action by one of the Air India pilots of closing both the engines’ fuel control switches seconds after take-off from Ahmedabad was an extraordinary mistake or a deliberate act (as does my previous piece in this blog). The Indian Air Accident Investigation Bureau confirms the pilot’s act of shutting off the fuel, and within about a year its report should be able to provide a verdict on why he did it.

Summing up safety in 2025, FlightGlobal said: “Apart from the Air India loss, almost all the accidents can be considered to have been “traditional” in nature. That is, they were caused by exposure to ordinary threats such as bad weather, pilots taking avoidable risks, or errors of omission or commission, bird-strikes, turbulence encounters and maintenance shortcomings.”

One of the primary reasons air travel is so much safer than it used to be is that the aircraft and engines are better engineered than they were forty years ago, and smart avionics give the crews more information presented more intuitively. There is a parallel between engineering advances in the avation and automotive industries. Anyone who owns a new car today recognises that its reliability and its technology is much better than cars built in the 1980s.

The theoretical downside of “smarter” aircraft is that they are highly computerised and thus more complex, but in practice that concern is not borne out because the systems are so reliable they rarely go wrong, and they are self-monitoring so the pilots are kept informed of systems health.

The human factors worry is that the sheer reliability means pilots may be lulled into a comfortable, non-critical mindset, so when something does go wrong they are startled and may react inappropriately. Again – theoretically – there is more that can go wrong because aircraft may still be traditional mechanical machines, but they are overlaid with software-driven sensors and computerised flight management systems. On the rare occasions when these go wrong, however, the crew may be confronted with a problem that has never presented before, so there is no checklist to deal with it.

For that reason, today’s crews in their basic training are still confronted with traditional problems like engine failure, but their advanced and continuation training is designed to inculcate a resilient mindset, based on flight priorities, paticularly when something unidentified has gone wrong: 1. Aviate, 2. Navigate, 3. Communicate.

Aviate: is the aircraft flying at the appropriate speed, height and attitude? Navigate: what is the aircraft’s position, is it heading in the direction it should be, and what is the fuel state? Communicate: report your situation to ATC, then work with other crew to deternine the best course of action to deal with the problem, and tell the cabin crew chief what is going on. Finally, while dealing with the problem, revisit your priorities over and over again: are you aviating right, are you navigating right, are you communicating what people need to know?

On this theme of training pilots to interface with the aircraft’s systems, the air transport industry – like all others – has to prepare to make good use of the next level of information technology: artificial intelligence (AI). In a thoughtful paper entitled Artificial Intelligence in Aviation, IFALPA (International Federation of Airline Pilot Associations) warns the industry to be ready to use AI with care to support the piloting task. It advises: “The role of AI in the operation of a flight should always be to support the humans in the system”, adding: “For this to be effective, whatever the intended capability of an AI system, it should only present options to a pilot, never a fixed outcome. There should also be transparency to the pilot as to how these options have been selected, and the level of confidence associated with them.”

2025 may have played out with a relatively small number of low-tech airline accidents, but we have to be ready for something different, and hopefully even better.