Airbus is not, at present, able to give specific advice to A320 operators based on information available from the Egyptair MS804 investigation, according to a report by Flightglobal senior journalist David Kaminski-Morrow.

Data transmitted by the aircraft’s ACARS messaging unit to the Egyptair operations centre is insufficient to point to a cause, he reports, explaining: “Airbus has already informed operators, via two accident information bulletins, that the available data is limited and that the analysis of the transmissions does not contain enough data to determine the accident sequence, Flightglobal has established.”

The Flightglobal report continues: “With the inquiry unable to conclude whether a technical flaw contributed to the crash, the airframer has been unable to provide any immediate advisory to operators.

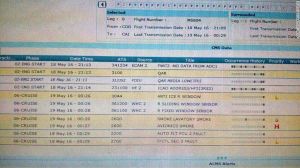

“Although seven ACARS maintenance messages transmitted in the space of 3min – between 02:26 and 02:29 Egyptian time – hint at the possibility of smoke and heat in the forward fuselage, there is no confirmation that the time-stamp of the messages correlates with the order of the trigger event and no clear indication of the precise time interval between them.”

The unknown factor is the “trigger event” referred to. The ACARS messages (see earlier blog entries) and the circumstances of the crew’s loss of control over the aircraft do not provide specific evidence to indicate either sabotage or a fault as the trigger event. But whichever it was, it appears to have generated fire that caused progressive electrical failures, and the crew’s loss of control over the aircraft ensued soon after that.

Floating wreckage and body parts recovered from the water where the aircraft crashed into the Mediterranean Sea north of Alexandria, Egypt, so far provide no clue as to whether sabotage or another cause brought the aircraft down. And the search coordinators have released no information about how widely the wreckage field is spread. This can be an indicator of whether the aircraft came down in one piece or had broken up in the sky, but after time the clues can be lost because the floating wreckage can be spread by sea currents and wind.

All this makes the recovery of the main wreckage and the flight data and cockpit voice recorders from the sea bed vital for the understanding of what caused the loss.